Blueprint of Digital Architecture

Summary

This report on the OBAMA-NEXT Blueprint of Digital Architecture outlines how project participants can live up to the stated promise to “ensure that the algorithms developed and applied are open sourced and documented”.

It identifies activities which participants are expected to engage in as they work on the development of the tools and methods needed to deliver the planned outputs and products. It introduces the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub Organization and explains how this provides a platform supporting participants in these activities. Participants can create repositories where they can manage and store the codes and algorithms being developed and to cooperate with others on this development. This allows code to be shared within the project and ultimately made publicly available. The platform provides features for version control and tracking changes and developments in code as well as facilitating integration of documentation and project planning. Project participants are encouraged to follow the best practices outlined here to ensure consistency across the various project activities, improving efficiency and security and ensuring longevity of the project outcomes.

The report also describes the how this integration of codes and documentation in repositories is linked to storage and publication of data in the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) as well as to permanent archival of code in the open repository Zenodo. The report includes a template for documentation of codes as well as guidelines for publication of data in EMODnet.

1. Introduction

The overarching aim of the OBAMA-NEXT project is to “develop innovative tools to monitor and describe marine organisms, from microbes to mammals, and ecosystem services across different habitat types in European coastal and marine waters”. This goal will be met by building, testing, and applying diverse tools, models, and algorithms that make use of a wide variety of measurements reflecting the functioning and diversity of marine ecosystems, habitats and species.

Data from sources identified in work packages 2 (pelagic habitats) and 3 (benthic habitats) is used by tools developed in work package 4 to provide information products that increase knowledge and improve the basis for better decisions for the management of marine ecosystems. The processing chains and information flows linking data sources from WP2 and WP3 with the tools developed in WP4 should be well-documented so that the results of analyses and any subsequent outputs in the form of tables, figures or other downstream datasets are reproducible and the steps taken to generate them are open and can be clearly followed. In some cases, the result of an analysis is the product, in other cases the tool or method itself is the product. The requirements for well-documented reproducible science apply to both.

The project proposal states that we will “ensure that the algorithms developed and applied are open sourced and documented”. In order to live up to this promise, the task of providing a “blueprint of digital architecture and exposure through repositories” (Task 4.2) has been defined. This report outlines how the work in this task helps the project participant to meet this requirement. The task provides the infrastructure where project participants can cooperate on the development and management of codes, algorithms, and tools and where they can publish the algorithms developed.

1.1. Aims

Within the scope of the OBAMA-NEXT project we have agreed on a definition of “digital architecture” as referring to a “common digital infrastructure for data processing, algorithms and models”. We have identified several different activities which are part of the process of developing tools. These activities are common to software development and project management in a far broader sense than the work of the OBAMA-NEXT project.

The work of Task 4.2 to provide a “blueprint of digital architecture and exposure through repositories” is guided by considering the needs of the project participants as they engage in these activities. This report outlines how the work done on this task supports project participants by providing infrastructure which enables cooperation for the development and management of codes and tools.

The range of analyses carried out, the different types of software tools employed, and the volumes and variety of data types utilised vary enormously within the project. Whilst it is difficult to encompass every conceivable situation where project participants will develop a new tool or information product (IP), project participants are strongly encouraged to follow the guidelines here to ensure consistency and quality in the management and documentation of tool development, across project tasks. The relevance of each activity will vary between tasks but considering all the activities and thinking about how each activity is relevant to their work will help project participants to give structure to the development process in their particular case and to ensure quality in the products they develop. We begin by defining the activities and tasks associated with development of tools before describing how the infrastructure developed addresses the needs of project participants in relation to these activities and helps them to meet the requirements of making their work open source.

1.2. Definitions

We describe here the activities which have been identified as being relevant to the development of tools, algorithms and information products in the project. These definitions are arranged roughly in order in which they take place during a project. This is not an indication that they should be addressed one by one. Archival of data and codes is the last activity in the list but this should be considered in the design and planning steps. During later stages of development, it may become necessary to return to the planning stage to revise and rethink the work necessary to complete the planned tasks.

| 1. Design | 5. Processing | 9. Publication of code |

| 2. Planning | 6. Testing | 10. Publication of data |

| 3. Coding | 7. Documentation | 11. Archival |

| 4. Sharing data | 8. Deployment |

1.2.1. Design

Work Package 6 guides the overall direction of the development of IPs by identifying policy needs and data gaps in relation to monitoring the health of coastal and marine environments. This is summarized in Deliverable 6.1 “Review, analysis and crosswalk of the data requirements of key policies” (Walton et al., 2023) . The question of which tools and information products are best suited to meeting these needs is outside the scope of this report, but it is nonetheless an important consideration. A clear understanding of the motivation for developing a tool and the requirements it should meet should be in place before the first lines of code are written. It is also necessary to consider how the products of a tool will be used to maximum effect, in accordance with the “Dissemination, Exploitation, and Communication” (DEC) strategy for the project (Leal et al., 2023).

Assuming that a tool or algorithm has been identified as relevant, a good design should identify the necessary components of the tool and map the steps in the collection, flow, and processing of data. Which data sources will be used? Where will data be stored and how will it be accessed before during and after processing? Which type of database or data storage will be used - simple spreadsheets or dedicated databases?

How and where will the processing of data be done - using cloud computing resources or on local computers? This will depend on the volume of data to be handled. Which software tools or programming languages are best suited for developing the processing steps? Python, R etc.? How will the results of this tool be used or disseminated? Will they provide input to other analyses? Will they be presented in a report or as an interactive dashboard for decision makers?

OBAMA-NEXT is a research project and not all these questions can be answered beforehand but giving thought to them as early as possible and before starting on the work of developing a tool will help to minimise the risk of potential problems and to ensure that project resources are employed most effectively.

1.2.2. Planning

Having established the motivation for development of a tool or algorithm and having developed an outline of the individual steps, which compose the task to be performed, the project participant(s) should begin to think in terms of timelines and resources for each of these steps. Some of this work has already been done in the planning of the project, establishing the external constraints for the individual tasks of developing each tool. In the same way as milestones have been set for ‘parent’ project, these should be developed for the task in hand. Resources should be allocated for the different tasks, both financial and personnel. Can we estimate how much time and effort is required for preparation of data before the “real” analysis can begin? Who has the competences necessary to do the coding of a piece of software or to perform a statistical analysis. A detailed timeline showing the responsibilities and milestones for key phases such as data collection, tool development, testing, and dissemination will help members of the team working on a task and other project participants to understand the expectations and ensure that products are delivered as planned.

The plan for developing a tool should also identify potential risks. These can be technical. Is there a risk that important data will not be available? Is there a risk that the intended methods do not give the expected results? There can be other risks. What is the “bus factor” for the task? This darkly humorous term refers to the potential risk resulting from key members suddenly being removed from a project. How many members of the team would have to be removed (e.g. if they were “hit by a bus”) to cause the task to stall due to a lack of knowledge or key competences. A plan should include contingencies to minimise the consequences for the project should any of these problems arise.

1.2.3. Coding

This activity refers to the work of writing the code for the tools, algorithms and scripts required for processing data, performing planned analyses and generating results. Guidance for best practices in writing code to ensure quality and consistency are readily available online. For example, PEP8 guidelines for Python or the “Turing Way” The turing way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research. (2022) includes more general guidelines for writing good quality code. This includes considering aspects of good code, naming of variables and files in a meaningful and consistent manner, using comments to explain functions and steps in your code, dividing separate tasks into modular functions which can be easily reused. These things make your code more readable and easier to maintain. This will save time when the inevitable happens and you need to return to a piece of code after months or years to fix a bug or make a change.

Even for the very simplest scripts or codes, using version control to maintain good quality code is still recommended. For more complex tasks, it becomes essential. The OBAMA-NEXT GitHub organization has been established precisely with this in mind (see the next section). Using version control simply means that we record the changes made to a set of files. Using version control is not dependent on the choice of programming language or the type of task being undertaken. These files organized in a collection called a repository where files relating to a particular task are collected. This allows us to trace the precise version of a code which generated a specific set of results, to revert to earlier versions of codes or to see which project member has made which changes. Guidelines for good practices in using version control and code maintenance are also widely available (e.g. again, the “Turing Way”, 2022). For example, documenting changes in code when submitting (“committing”) changes so that they are linked to a particular issue which was solved or to a desired change in the functionality or features of a tool. We recommend generating release versions of tools, using a three-part numbering system to indicate the increments in development (e.g. 1.2.3 where the first number, ‘1’ indicates a major release, ‘2’ a minor development and ‘3’ indicates a “build” version following a bug-fix or other small change).

If your work depends on third-party code from outside the OBAMA-NEXT organization, steps should be taken to ensure that this code is safe to use. The GitHub “Code security” documentation includes guidance on ensuring safe use of dependencies and maintains a database of current “advisories” regarding security vulnerabilities and other issues (e.g. malware) in opens source software. Maintaining good code also entails keeping your code up to date with developments in any external sources and ensuring that this is done safely. Where possible, repositories should be “forked” so that updates are controlled.

1.2.5. Processing

For some tasks this is an essential consideration. Setting up automated procedures to process data on a regular basis will be familiar to anyone working with satellite images. Already thinking in automation of quality control procedures for cleaning data from the design phase can make processing of new data less time consuming. Making processing steps automatic makes results consistent and reduces the risk of human error. This activity may seem less relevant for some tasks. But even a task which may be thought of as a “one off” or “once only” analysis can benefit from thinking about processing in a structured manner. It is very seldom that a “once only” analysis turns out to be something which is only done once. A change in input data or discovering an error in a data-processing step can make it necessary to rerun several other steps “downstream” of the changes. In these cases, there is great benefit in having a well-structured workflow where processing steps are isolated as “modules” and where a single step can be modified without affecting the entire chain of processing steps. This activity is closely related to the design activity and to how the code and sub-tasks are organised.

1.2.6. Testing

Here we are referring not only to testing the quality of overall results from a tool but also testing each step in the processing chain. Does each component function as expected and give the results required for the next step in our analysis? What happens when an unexpected or unrealistic value is supplied to a function? Will the whole processing workflow break down or, worse, will it pass undetected causing an error in the overall results which can be difficult to trace?

Performance and speed of processing can also be important considerations. If the goal is to produce a web-based visualization, does the website perform well? How does the performance change if there are many concurrent users. Testing processing steps and analysis on smaller example datasets is an efficient way to find errors and inconsistencies before scaling up the analyses to full datasets. Again, these concepts may be familiar to project participants used to working with tools that perform computationally intensive operations on very large datasets, but the ideas can also be relevant and improve productivity even for smaller tasks.

1.2.7. Documentation

Producing comprehensive documentation to describe all tools, processing steps and workflows is necessary to ensure reproducibility and transparency. Documentation should be thought into the development process as early as possible. This is easier than trying, retrospectively, to remember what was done and to document afterwards. This activity is also closely related to good practices in coding and structuring projects.

Technical documentation should cover the details of the code and how the tools and their processing steps are structured. Including of comments in code has been mentioned already. In this way, good code becomes self-documenting. This can include diagrams showing the flow of data through the different steps.

User manuals should help end users to understand the underlying functionality as well as giving clear instructions to enable them to use the tool or run the analysis. If the tool is a piece of software, the manual should explain how it is installed. Providing examples of usage will help users to understand and learn how to use the tool. Suggesting troubleshooting tips where things go wrong can prevent frustration and help to avoid negative responses from intended end-users. Tutorials and examples can take many forms. They can be simple documents, websites, interactive notebooks, or video tutorials. The choice of delivery method should be appropriate to the users in question. Good documentation of the OBAMA-NEXT tools and products will help to maintain their relevance and usage beyond the lifespan of the project and to ensure their adoption by as wide an audience as possible.

1.2.8. Deployment

This is another topic which may, at first, seem relevant only to operational web-based tools and web developers will be familiar with this concept. It can aid productivity even for smaller projects and development tasks. For example, Docker is a popular tool for “containerizing” an application. Consider a tool that requires a particular software tool or a particular set of R packages to be installed before it can run. What happens when we want to run the tool on a new computer? We will have to install the required components on which the tool depends before we can run it. Can we avoid potential problems arising from installing slightly different versions of these components?

Docker allows us to pack all required “dependencies” - everything needed to run the tool - in a “container”. When the container is deployed, we can be sure that all necessary prerequisites are in place to run the tool. What is more, we know that the versions of operating system and software packages are identical with the ones we used earlier to develop the tools.

1.2.9. Publication of code

The code and algorithms developed in OBAMA-NEXT should be made openly available. This can be done using the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub organization (see 2.1 below) though there is no specific requirement as to where the code should be made available. Wherever the code is published, it is essential that it is well documented, as described in the section above. Sharing of code should also be aligned with the OBAMA-NEXT DEC strategy for exploiting the results of the project to give the greatest impact. Licensing of the code is a small but important detail. Using a suitable open-source license will ensure that any derivative works are obligated to give appropriate credit to the original developers and to the OBAMA-NEXT project.

Sharing code openly is not only a requirement but it brings with it many benefits. Sharing code promotes transparency and reproducibility. It allows for a collaborative process bringing in a broader community of researchers who can provide important feedback to OBAMA-NEXT participants. It will allow other scientists to build on the work of OBAMA-NEXT and to make further advances or improvements, increasing the potential for maintaining and extending the useful life of the tools developed.

1.2.10. Publication of data

As described above, we distinguish between activities involving data-sharing within the project where the data will be used in the development of tools and algorithms and the “publication” of data where a dataset can be made publicly available for use outside the project. This could be observation data gathered during the project and which could be useful for other researchers. It could be derived data products or outputs generated by OBAMA-NEXT tools or analyses. Irrespective of its origins, data to be shared should be well-documented, following guidance in the DMP and in accordance with FAIR principles, and include complete metadata ensuring that the scientists who have produced the data are properly recognized when the source of the data is cited.

Publishing data through the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) is an important component of the DEC strategy for OBAMA-NEXT, where data can be made permanently available for future use. To this end, guidelines for publishing data through EMODnet are given below.

1.2.11. Archival

As described above, sharing the codes and data developed by OBAMA-NEXT will help to ensure that the impacts of the work last beyond the lifetime of the project and continue to be useful long afterwards. Regarding archival of data, anything published in EMODnet can also be considered as permanently archived. The DMP also includes guidelines for permanent archival in an OBAMA-NEXT Zenodo repository OBAMA-NEXT: Observing and Mapping Marine Ecosystems - Next Generation Tools | Zenodo. Zenodo can also be used to archive codes. Whereas a GitHub repository provides a platform for active development of code, the Zenodo repository can be used to store a snapshot of the code for a tool or algorithm, assigning it a unique identifier such that this version of the code can always be found. This provides an additional safeguard to ensure that the code developed during OBAMA-NEXT remains available for future use. Again, it is essential that the archived version of the code is accompanied by the documentation necessary to run the tool or algorithm.

2. Common digital infrastructure

2.1. GitHub Organization

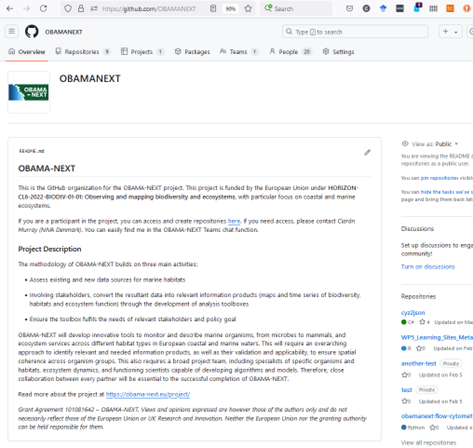

An OBAMA-NEXT GitHub “organization” has been established where project participants can store and manage the codes and scripts for the tools and IPs they are developing (see Figure 1). As well as enabling cooperation within the project or within smaller teams, this is also intended as the platform where code can ultimately be shared openly outside the project, allowing for further development and giving the tools and IPs a life after the project.

2.1.1. GitHub

GitHub is widely used for collaborating on development of software and version control. It is a web-based platform where the essential unit of operation is a “repository”. This is a location where the files related to a single software project or tool are collected. The repository also stores information on the history of the project, tracking the changes made. A repository is hosted online by GitHub but a project participant can work in a local copy of the repository and then update the online repository with their work.

Developers can work concurrently on the same task or tool. For example, a project participant can create a “branch” of the code to develop and test a new feature or function, or fix a bug, without affecting the main code and then when they are ready, they can merge their contributions to the main code. The use of version control in general and specifically GitHub is well described elsewhere e.g. “The Turing Way” The turing way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research. (2022).

A GitHub “organization” refers to a collection of users or developers working in the same team or organization, in this case the OBAMA-NEXT project. The members can set up different repositories for code under the umbrella of the organization. Access to repositories can be finely managed allowing the whole organization or selected individuals or teams to view or make changes to code. GitHub is not the only platform which is suitable for version control. It is itself not open source but is free to use and is used extensively. It is already familiar to many project participants. New users who are familiar with other online tools or regularly use with other common software tools should have little difficulty in starting to use GitHub. This choice of platform comes, therefore, with minimal “initial cost”.

2.1.2. How can we use GitHub?

Table 1 shows the development activities we have identified, where a tick in the column “GitHub” indicates an activity which GitHub can help with. An activity without a tick requires other resources or an alternative platform. For example, “Processing” the step of actually running a code to perform some operations on data must take place outside GitHub, on a local computer or perhaps on a cloud computing facility (“others”). A tick in brackets for “Sharing data” indicates that there are limitations on size of data.

| Activity | GitHub | Zenodo | EMODnet | others |

| Design | ✔️ | |||

| Planning | ✔️ | |||

| Coding | ✔️ | |||

| Sharing data | (✔️) | ✔️ | ||

| Processing | ✔️ | |||

| Testing | ✔️ | |||

| Documentation | ✔️ | |||

| Deployment | ✔️ | ✔️ | ||

| Publication of code | ✔️ | |||

| Publication of data | ✔️ | |||

| Archival | ✔️ | ✔️ | ✔️ |

As well as providing for version control, an important feature of GitHub is the relative ease with which code can be documented and this documentation can be integrated within the code repository. Users can quickly and easily generate documentation using “markdown” a text-based language designed to produce clear and readable documents. It requires no knowledge of programming and formatting of text is very simple. The introductory page of the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub site (Figure 1) is written in markdown.

GitHub has other useful features for project management. The task of developing a complex tool can be separated into subtasks. Tasks can be assigned to individuals or groups. The tasks and subtasks can be viewed in tabular form or as a Gantt chart, to visualise progress over time. They can also be viewed as a “Kanban”1 board. These tasks can also be linked to specific versions of code and related changes.

At the more advanced level, GitHub “Actions” can be used to automate deployment or testing. These can be set up so that a change in code triggers other events such as building and deploying a container (see 1.2.8 above) so that a web application is automatically updated following a modification.

All these features will facilitate cooperation within the project between work packages and tasks, between developers of tools and methods and those testing them in Learning Sites (LSs). Ultimately, it will enable developers and researchers outside the project to view and replicate analyses and results, promoting openness and transparency as well as providing the opportunity for them to reuse tools and code in their own work or to collaborate with OBAMA-NEXT researchers and contribute with improvements and updates to existing tools.

2.1.3. What needs to be done outside GitHub?

Though version control works best with text files such as code for programming languages like R, Python, etc. there are no restrictions on what type of files can be stored in a GitHub repository. For example, a small file containing input data to be used in an example demonstrating how a tool or algorithm functions can be added to a repository together with the code which is needed to run the demonstration as well as an output file, perhaps a map in an image file format.

Files greater than 100 MB cannot be stored in a GitHub repository and though there is no official limit, GitHub recommend that repositories do not exceed 1 GB in total size. For smaller tasks this might be sufficient, and the repository can be used to store all data files used as input and all output as well as the code used to process them. For tools and IP processing or producing larger volumes of data, data storage must be outside GitHub. For sharing data products outside the project and for archiving them permanently, Zenodo and EMODnet are better suited.

Whilst work on a tool or software remains active, GitHub is ideal for sharing code openly, allowing outside contributors to make suggestions for improvement or create their own versions of the code, building and advancing the work of OBAMA-NEXT. Although GitHub does have a system for “release” versions to capture a unique snapshot of a repository at a particular state, it is not designed for creating a permanent archive of code. Zenodo is intended for long-term preservation, and it is strongly recommended that project participants use Zenodo to archive their code at the time of publication of related work or at the end of the project. This archival process can though be integrated with GitHub so that a release version of a repository is automatically saved in Zenodo and given a unique Digital Object Indentifier (DOI).

As described above, the step of running a code or tool to produce an output or running a server hosting a web-based visualization is done outside of the GitHub repositories. This requires computational resources e.g. in the form of a local standalone PC or a cloud computing server. Again, GitHub Actions can be set up so that modifications in code trigger a restart of the compilation of code to build a piece of software or an update to a website.

2.2. Guidelines for usage

There is no single “correct” way to manage the development of code. There are a diversity of tasks and activities within the OBAMA-NEXT project and a great variation in the familiarity of project participants with tools for version control and for software development. These instructions are intended to ensure that there is a coherent and common approach to managing these activities across the project. They should be viewed as the project organisation’s guidelines for best practice and should provide users with a structure for thinking about the best way to manage their code. They are not exhaustive, and users, particularly experienced users of GitHub should not be constrained by these guidelines. On the contrary, feedback and continual improvement of the common approach to managing tool development is welcomed.

Many of the participants in OBAMA-NEXT will be familiar with GitHub. Others might never have heard of it. As described in the GitHub guide, “GitHub is a code hosting platform for version control and collaboration. It lets you and others work together on projects from anywhere.”

Using version control we avoid the all-too-common situation of finding ourselves with a set of files called: my_file.txt, my_file_edited.txt, my_file_final.txt and my_file_final_final.txt. Which one is the latest? And which one relates to which set of calculations, datasets, figures, etc.? We avoid keeping multiple copies of the same file after editing. Instead, each time we alter a file and create a new version, we save it to our repository, replacing the original (it can be more complicated than that, but it doesn’t need to be). It is then possible to follow the changes made over time and to easily find previous versions if we need to return to them.

“Tools” “scripts” “software” “codes” - what do we mean? This is meant very broadly. Though GitHub works best with text-based files such as Python code or scripts from other programming languages, you can also save MS Office or other binary files. At its simplest, you could save a simple text file with a list of things you did.

The single most important advice for users of the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub repositories is to act in the spirit of making your work transparent and reproducible. This requires careful documentation and explanation of your codes and tools. Trying to document a tool or IP retrospectively, after completion of the development work is very difficult. Making documentation a central part of the development work from the outset, creating an outline for the structure of steps involved in the task you are setting out to solve and carefully documenting each step as you work on it will help to ensure that your work can be easily shared with and understood by others. It also benefits you, the user, when inevitably you are required to return to older work to make a modification which is needed or fix an error which has been discovered.

A suggested structure for documentation is as follows:

2.2.1. Description and background

Documentation of your code/tool should begin with a brief description of what it does, and why. What is the context for the development of this tool? Which problems does it address and what are the goals we hope to achieve by creating this tool or providing this Information Product?

2.2.2. Prerequisites

Include a list of all software or packages which your tool requires to function correctly. Is it dependent on proprietary software? A banal example - if you made an Excel spreadsheet, then Microsoft Excel is a prerequisite. Which version of the software have you used? Are there requirements regarding hardware or processing capabilities? Which operating systems has the tool been tested on? Are there other tasks in the OBAMA-NEXT project which your task is reliant on?

Document the dependence of your tools on code residing outside of the OBAMA-NEXT organization, and show what steps have been made to check the provenance of this code and ensure that there are no security risks. Check the GitHub “Code security” documentation and database of current “advisories” regarding security.

2.2.3. Input

Document the input parameters/data required by your code/tool. Describe the type, structure and format of the data expected. Provide explanations of the parameters and requirements regarding expected range of values. Will your tool catch values outside of an expected range? Give examples for each type of input and describe how it should be prepared.

2.2.4. Output

Describe the expected output and its structure and format. Give examples and explain how the outputs should be interpreted. An illustration linking an example of an input dataset with the expected output gives the user a way to check that they are using the tool correctly. Are there other tasks in the OBAMA-NEXT project which depend on output from your work?

2.2.5. Methodology

What are the theories and principles underlying the methods and algorithms in your tool or which have been used to generate the IP (information product)? Include references to relevant literature.

2.2.6. Usage Instructions

Include step-by-step instructions on how to use the code/tool. If an installation step is required, instruction for this should be included. Provide examples of usage describing sample inputs and the expected results (see “Output” above). Explain any options or configuration that the user can change. Describe how the code/tool handles errors or exceptions. Include common error messages and their meanings. What can go wrong and what can be done to fix common issues?

2.2.7. Contributors

List the people who have contributed to the development of the code/tool/IP. Any additional help aside from the main development can be included in acknowledgments. Contact details for the main developers or persons responsible for maintaining the code should be included.

2.2.8. Version History

Keep track of the version history of the code/tool. This includes the date, version number, and a description of the changes made. As described above, follow three-component version numbering system to indicate the relative importance of changes in code with major releases, minor developments and “build” versions. Document the plan for keeping your code up to date with development in external dependencies and for ensuring that this is done safely, including “forks” of external repositories.

2.2.9. License

Specify the type of license which applies to how the tools or code can be modified or distributed. Explain any restrictions on usage, stating what is allowed or not allowed. Include the text of the license agreement. Including a license provides clarity for potential users of your code or tools and ensures that OBAMA-NEXT will be credited for its work when this is used outside the project. Detailed guidance on how to choose a suitable license is readily available online e.g. “The Turing Way” and guidance for managing intellectual property rights in EU-funded projects can be obtained from the European Commission IP (Intellectual Property) Helpdesk. Annex 5 of the project grant agreement outlines the rights obligations of the project participants to protect and exploit the research outputs (“scientific publications, data or other engineered results and processes such as software, algorithms, protocols, models, workflows and electronic notebooks”), and other intellectual property, including the sharing of outputs between project participants, with EU institutions and with third parties. It is essential that the correct license is chosen stating the conditions for exploitation and use of the outputs, to protect the rights of the project partners, to meet obligations under the grant agreement and to align with the project DEC strategy.

2.3. Publication of data products

Sharing products and outputs with other researchers is key component of the DEC strategy for OBAMA-NEXT. By making them available for future development and further exploitation, we can maximize the long-term impact of the results of the project. As described above, the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub organization provides a platform for sharing and documenting the codes and methods developed, both within the project and outside.

GitHub is, however, not a platform suited for either publication or permanent archival of datasets. Other platforms which offer this facility include Zenodo, which is open for submission of content from all fields of research and not limited to marine environmental data. Whilst Zenodo has guidelines for documentation of submissions and for providing metadata, these are not enforced, and data can be published with a minimum of documentation and in any format.

The European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) is a network of partner organizations supported by the EU, collaborating with the goal of making marine data accessible. The OBAMA-NEXT strategy for exploitation of IPs and other data products is closely aligned with the aims of EMODnet in increasing accessibility to marine data and to promote its relevance for informing policy decisions.

Submitting data to EMODnet is more complicated than publishing in a Zenodo repository. This is a “feature”, not a “bug”. Researchers who wish to submit data to EMODnet must meet requirements regarding documentation and provision of metadata. Data must be organized in an approved format. Additionally, the submission process requires approval from a partner organization in EMODnet before it can be published. These requirements contribute to ensuring that data published in EMODnet are well-documented and thus easy to find and to reuse.

OBAMA-NEXT project participants are obliged to follow FAIR principles by making their data available through EMODnet, both IPs as well as other data collections gathered during the project which may be useful to other researchers. The necessary preparation of data and the submission process are explained in detail on EMODnet Data Ingestion Portal. Furthermore, several OBAMA-NEXT participants are members of EMODnet partner organizations and can offer guidance in preparing data for submission. The EMODnet portal should be considered an integral part of the OBAMA-NEXT digital infrastructure and is thus the logical “final stop” for data generated, where it can be shared and reused in new research and new applications. An overview of the submission process is outlined in Annex 2.

3. Next steps

In order to meet the promise to “ensure that the algorithms developed and applied are open sourced and documented” the OBAMA-NEXT project proposal states that we will provide a “blueprint of digital architecture and exposure through repositories”.

This Blueprint of Digital Architecture (Deliverable 4.2) outlines how the established infrastructure and the guidelines developed here form a best-practice guidance document supporting the testing of tools, models and information products in the OBAMA-NEXT learning sites.

Next steps include testing in Learning Sites and this generic guidance provides the infrastructure 1) where Learning Sites and project partners can cooperate on the development and management of codes, algorithms, and tools and 2) where they can publish the algorithms developed. It should be emphasized that this guidance is intended as a living document. We foresee an iterative process with feedback from the testing in learning sites and subsequent improvements and updated of the document. Please refer to the OBAMA-NEXT GitHub site for information about revisions and to see the most recent version.

References

Annex 1

Template for documentation of code repository

Repository URL:

Document date:

Completed by:

Description and background

Documentation of your code/tool should begin with a description of what it does (and why)

Prerequisites

Is your tool dependent on proprietary software? A banal example – if you made an Excel spreadsheet, then Microsoft Excel is a prerequisite. Which version of the software have you used? Which operating systems have you tested your tool on? Are there other tasks in the OBAMA-NEXT project which your task is reliant on? Document steps taken to check the provenance of code residing outside of the OBAMA-NEXT organization to ensure that it is safe to use.

Input

Document the input parameters/data required by your code/tool. Describe the type and format. Give examples for each type of input.

Output

Describe the expected output. This includes its type, format, and how it should be interpreted. Does output from your work feed in to other tasks in the OBAMA-NEXT project?

Methodology

Describe the logic, algorithms, or methodologies used in the code/tool, with references.

Usage Instructions

Include step-by-step instructions on how to use the code/tool. This can include installation instructions, example usage, and any necessary configurations. If relevant, describe how the code/tool handles errors or exceptions. Include common error messages and their meanings. What can go wrong and how can it be remedied?

Contributors

List the people who have contributed to the development of the code/tool.

Version History

Keep track of the version history of the code/tool. This includes the date, version number, and a brief description of the changes made.

License

If applicable, include any licenses which specify the terms under which the code/tool can be used or distributed. The terms of licensing should be in accordance with the rights and obligations of project partners, as outlined in Annex 5 of the grant agreement.

Annex 2

Submitting Information Products to EMODnet

This annex provides a very brief outline of the process for submission of data to EMODnet. It is not exhaustive and further details regarding different stages in the process can be found through the links included below. Publishing a dataset in EMODnet involves several steps which require an effort on your part. This is necessary to ensure that your data can be easily found and reused. Publication of data in EMODnet will contribute to the visibility of your work and also to the wider goal of improving the availability of marine data and enhancing its relevance. A very useful overview of a wide range of EMODnet guidance documents and publications can be found at: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/tools-guidelines.

This site provides further links to guidance for specific data themes, for different parts of the submission process and to tools for managing and preparing data. It is unnecessary to duplicate the comprehensive guidance and advice produced by EMODnet. Participating institutions in the OBAMA-NEXT project include member organizations in the EMODnet network. Assistance and advice are readily available by contacting WP4 members who can provide more information.

Registration and/or authentication

Before your data can be submitted, you must first register with the MarineID service which is used by EMODnet and other portals to identify users https://www.emodnet-ingestion.eu/data-submission/how-to-register-as-data-submitter. If you have registered previously, you should log in with your existing MarineID.

Data format and metadata

General guidelines regarding data format are given by the EMODnet data ingestion portal. Following these guidelines ensures that data are not recorded in a proprietary format which limits their accessibility for users without access to specific software tools but can be read by all. Data to be submitted must also be accompanied by metadata which provide all necessary information identifying the organizations and/or persons responsible for creating or collecting the data, the type of data being submitted, any measurement instruments, analytical techniques or methods used, as well as geographical and temporal location and coverage and any identifiers used such as station or sample numbers. A very detailed explanation, with examples, of the “Submission process for contributing maps of seabed habitats and coastal wetlands to EMODnet” can be found at: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/sites/emodnet.ec.europa.eu/files/public/Seabed%20Habitats/EMODnet_Guide_for_submitting_seabed_habitat_maps_V3.pdf

Phase I Publishing

EMODnet distinguishes between two separate phases in the data submission process. In the first phase, a data submitter uploads a dataset or collection of datasets to the EMODnet ingestion portal (https://www.emodnet-ingestion.eu) accompanied by a minimal set of metadata and documentation. At this stage an ingestion portal manager assigns a data centre which will handle the further processing of the submitted data, depending on the type or theme of the data. In dialogue with the submitter, the data centre will review the submission before publishing it “as is” with the accompanying documentation.

Phase II

In the next phase, the data centre will prepare the published data sets for long-term storage in a suitable thematic portal and for sharing with the appropriate data infrastructures. This step will likely involve dialogue with the submitter and may require them to provide further information or metadata. This two-stage process allows the shared data to be made available as quickly and easily as possible whilst still ensuring that the permanent archival of datasets is harmonized with existing infrastructure and standards.

Footnotes

“Kanban” is a Japanese word used for this visualization originating from Lean manufacturing management methods. The board resembles a physical (white- or black-) board where tasks are represented as cards on the board. Cards are placed in columns “To Do”, “In progress” and “Done” and progress can be followed as cards are moved from one column to the next as tasks are started and finished.↩︎